L.M. Montgomery’s Green Gables

L.M. Montgomery’s Green Gables

Alan MacEachern

Green Gables Heritage Place in Cavendish might just be the most famous house in Canada, thanks to its association with L.M. Montgomery’s Anne of Green Gables, but the nature of that association always requires explanation. No, the author was not born there. No, she did not live there while growing up or writing the book. No, it was never the home of Anne, a fictional character. Yes, it was an inspiration for the book’s titular location—but not the only one. All these clarifications signal just how limited the association really is. But it was one that grew stronger over time, for Montgomery herself as much as anyone.

Before it was Green Gables, the farm belonged to Margaret and David Macneill (siblings) and then Ernest and Myrtle Webb

Before Anne

Before it was Green Gables, this was a typical Prince Edward Island farm property: a long, thin parcel of 100-plus acres, stretching to the shore, with a solid but unspectacular 19th-century two-storey farmhouse at its centre. While Montgomery was growing up, it was owned by her elderly relations, siblings Margaret and David Macneill. Maud lived a few farms over and would cut through the Cavendish schoolyard and the neighbouring woods to arrive at “Lover’s Lane,” a forested path winding down the back of the Macneill property. It was this part of the Macneill farm that enchanted the future author: as a young woman, she wrote rapturously about Lover’s Lane in her journal any number of times. Of the Macneill house and fields, not at all (with the exception of her "dear den" bedroom).

In the mid-1890s, a young relative, Myrtle Macneill, moved in with Margaret and David, and became good friends with her cousin Maud. In time, Myrtle married Ernest Webb at the Macneill house and, in time, the Webbs took over the farm. With a friend nearer in age living there, Montgomery likely visited the house more than in the past, but there is no indication the house took on great meaning for her; the Webbs were not even living there when she wrote Anne.

Myrtle Macneill, standing outside Montgomery's home in Norval, Ontario, circa 1936.

Literary Pilgrims

Following the publication of Anne of Green Gables in 1908, literary pilgrims 1 descended on Cavendish searching for the locations that inspired the book—or expecting to find its actual sites. As early as 1911, Saturday Night magazine, in an imaginary exchange with Montgomery, chastised her for making P.E.I. so attractive it was sure to be overrun with tourists: “Why, one of the midsummer dreams of the Canadian traveller is to find Green Gables and catch a glimpse of Anne.” 2 Because the Lover’s Lane on the Webbs’ property was known to be the model for the one in the book, its farmhouse was increasingly also assumed to be Green Gables. There was another Cavendish candidate, however: Montgomery’s childhood home. But when the new owner of that house tired of the attention from tourists and tore it down, the Webb home became the unrivalled “Green Gables.”

Montgomery was flattered but bemused to have created so vivid a fictional setting that it spawned a real-world facsimile. She insisted on maintaining credit for her artistry—“Green Gables was practically imaginary,” she wrote 3 —and corrected alleged inspirations that were entirely wrong (such as that the pond at the front of the Webb farm was the Lake of Shining Waters). But she also became actively involved in solidifying the association between Green Gables and Green Gables.

Green Gables, Home

A tourist postcard like the ones Myrtle may have sold.

Because of all the public interest in their home, Myrtle and Ernest Webb opened it to summer boarders beginning in the early 1920s. Myrtle sold Green Gables-themed postcards and china to tourists, as well as copies of Anne of Green Gables autographed by the author. In her journal, Montgomery bemoaned the growing commercialization of Cavendish and how her literary career had contributed to it, but she never included the Webbs in this critique. She never complained, for example, that the Webbs themselves had come to call their home Green Gables.

The house was fast becoming part of her brand. The house promoting the books, as surely as the books promoted the house.

And the author was just pleased that the Webbs were maintaining it so tastefully.

But beyond commercial considerations, Green Gables also became a refuge for Maud. Having moved to Ontario, she now made it a focal point of her annual return. Lover’s Lane and the farm’s other natural attractions—including, as she told her journal, “what is now known, thanks to Anne, as ‘The Haunted Wood’” 4 —still beckoned, but so did the house itself. It was the closest she could get to a return to childhood, and more peaceful than her adult domestic life. Describing a stay at the Webbs’ in 1929, Montgomery wrote,

This evening I had a “home” evening of the kind I thought had vanished from the earth. We all sat in the “sitting room” as it is still called there. The chill of the autumn evening was banished by a cosy wood fire. I did a bit of embroidery, Myrtle sewed, Ernest read, the girls wrote letters, the kittens frolicked—we talked when we felt like it and kept silence when we did not. And there was a friendly “kerosene” lamp on the table, casting a mellow glow over all. 5

As always with Montgomery, it is difficult to separate her reality from her construction of it. Although she would later call the Webbs’ “my second home” and claimed that “whenever I went back to the Island I have made my headquarters there,” Green Gables was in reality only one of several homes she regularly stayed in when back on P.E.I. 6 Likewise, though it was widely believed she stayed in what had been christened “Anne’s Room” when at the Webbs, they in fact put her up in a room across the hall. 7

Green Gables, Destination

Cavendish grew ever more popular with tourists in the 1930s, with Green Gables its centrepiece. It got so that on weekend days in summer, a hundred cars would park directly on Cavendish Beach—not coincidentally, at the north end of the Webbs’ farm. In 1936, when inspectors for the Dominion Parks Branch toured the Island in search of a site for a national park, they were drawn to Green Gables house because of its clear mass tourism potential and because of their confidence that only a park could manage such tourism in perpetuity.

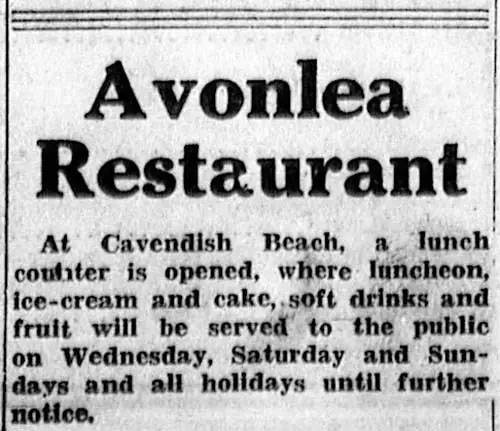

An ad from the Charlottetown Guardian, June 30, 1928, advertising the "Avonlea Restaurant."

Montgomery's remarks to the Toronto Globe on her trip to P.E.I. in 1936.

Montgomery was so closely associated with Green Gables by this point that she was informed of the Parks Branch’s interest well before the Webbs themselves were. Initially, she despaired as to what it would mean for the Webbs and for Green Gables itself: “Because of Anne forsooth!! … [W]hen I love a place is it not doomed?” 8 But she became reconciled to the expropriation when she learned that the Webbs would be kept on as caretakers of the home. She was content, she told the Toronto Globe, to know that “Anne’s haunts will be preserved.” 9 Prince Edward Island National Park did more than preserve them: it created them, continuing Green Gables’ transformation from a typical Island farmhouse to the idyll of Montgomery’s imagination. The landscape was tamed and prettified—flower gardens replacing vegetable gardens, a golf course replacing farmer’s fields—and the straight laneway was rerouted to offer a more romantic, winding entrance to the homestead. Shutters were installed on the house and, for the first time, the gables were painted green.

Montgomery returned to Prince Edward Island only twice after the park’s creation. The first time, in autumn 1939, was an escape from stresses personal and global, ranging from depression to the declaration of war. Seeing what the park had done with Green Gables reinvigorated her. Myrtle Webb recorded in her journal that “Maud has been getting lots of pictures of the place and loves every bit of it. She is feeling much better since she came.” 10 The second time was in April 1942, after her death in Ontario. Her body was brought home to Prince Edward Island and a wake held, 11 not in the home of relatives or a local church, but in the dining room of Green Gables. Despite being another family’s home and part of a national park, Green Gables was by now indisputably, inescapably L.M. Montgomery’s.

1 See Sarah Conrad Gothie, "Playing ‘Anne’: Red Braids, Green Gables, and Literary Tourists on Prince Edward Island,” Tourist Studies, vol. 16, no. 4, Dec. 2016, pp. 405–21, or her forthcoming project on Montgomery “pilgrims”; Diane Tye, “Multiple Meanings Called Cavendish: The Interaction of Tourism with Traditional Culture,” Journal of Canadian Studies / Revue d’études canadiennes, vol. 29, no. 1, Spring 1994, pp. 122–34; or Nicola MacLeod, “‘A Faint Whiff of Cigar’: The Literary Tourist’s Experience of Visiting Writers’ Homes,” Current Issues in Tourism, vol. 24, no. 9, 2021, pp. 1211–26. Back

2 Anne E. Nias, “Interviews with Authors,” Saturday Night, 28 October 1911. Back

3 My Dear Mr. M.: Letters to G.B. MacMillan, edited by Francis W. Bolger and Elizabeth R. Epperly, Oxford, 1992, p. 180. Back

4 October 13, 1929, Complete Journals: The Ontario Years, 1926–1929, edited by Jen Rubio, Rock's Mills Press, 2017, p. 299. Back

5 September 24, 1929, in The Selected Journals of L.M. Montgomery, Volume 4: 1929–1935, edited by Mary Rubio and Elizabeth Waterston, Oxford University Press, pp. 9. Back

6 Alexandra Heilbron, Remembering Lucy Maud Montgomery, Dundurn Press, 2001; and Webb diary. Back

7 Heilbron, Remembering LMM; and Webb diary. Back

8 July 12, 1936, The Selected Journals of L.M. Montgomery, Volume 5: 1935–1942, edited by Mary Rubio and Elizabeth Waterston, Oxford University Press, 2005, p. 80. Back

9 The Globe, November 7, 1936, p. 21. Back

10 Webb, GG Diary, 13 October 1939.Back

11 Three years later, Parks Canada informed the Webbs that they were to move out of Green Gables, on two weeks’ notice. Without the author to advocate for the Webbs, Parks Canada was free to complete the house’s transformation to a shrine to her and her creation. Back